Farming in the Shadow of Patents

The horizon was barren - not a single sapling was in sight. The black, dried soil was evidence of the farmer’s expectations of lush fields of cotton plants that promised them a better tomorrow - dying.

The story no longer remains about crop failure. The looming climate crisis, erratic weather patterns, the privatisation of agriculture and increased food insecurity – access to climate-resilient seeds has become a matter of survival. These seeds are not genetically modified (GM) but rather gene-altered – changed at a molecular level to be to withstand conditions of draught, heat and pests. The patent regime applicable on GM seeds have gone a step further when it comes to gene-altered seeds, creating tighter patent control.

Most gene-altered seeds are more expensive to buy and heavily patent-protected.

“The irony is that we were asked to pay for seeds that cannot survive such temperatures.” said Dr. Leela Rao, who works in the agricultural department of a local university in Andhra Pradesh. Her eyes held the hopelessness of someone who was aware of fighting a losing battle in cotton cultivation.

India’s cotton belt is dying. Farmers haves seen crops fail; yield reduce and ends not meeting. The planet was warming rampantly and seeds that were modified to provide abundance, now yielded nothing.

Further North, the Delhi High Court was a battleground between a giant agricultural MNC from the United States Monsanto and smaller Indian seed firms. The question being debated was whether a seed could be patented - especially in a country where food insecurity was a major problem.

The Indian Patent Act clearing prohibits the patenting of plants or seeds – they were public goods and a major part of food security. Yet, the Monsanto case was exceptional in its outcome – while the High Court of Delhi upheld the rights of the farmers, the Supreme Court of India allowed Monsanto to patent Bt Cotton seeds genetically modified to increase yield. The decision was the judicial endorsement of the commodification of food. Companies were in-charge now.

The decision was not made in the isolation of the national landscape but echoed the happening on the global scale. The World Trade Organisation has implemented the TRIPS Agreement which allowed the patenting of plant variants. Essentially the Act allowed companies to own seeds – cutting into age old-practices of seed exchange that was practiced by farmers in most South-Asian and Southeast Asian countries. While India did try to protect some interests of its farmers through the Protection of Plant Varieties and Farmers’ Rights (PPVFR) Act by balancing the needs of breeders and farmers, but the Monsanto case proved that only big companies would win.

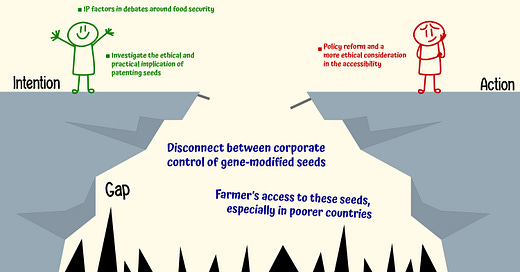

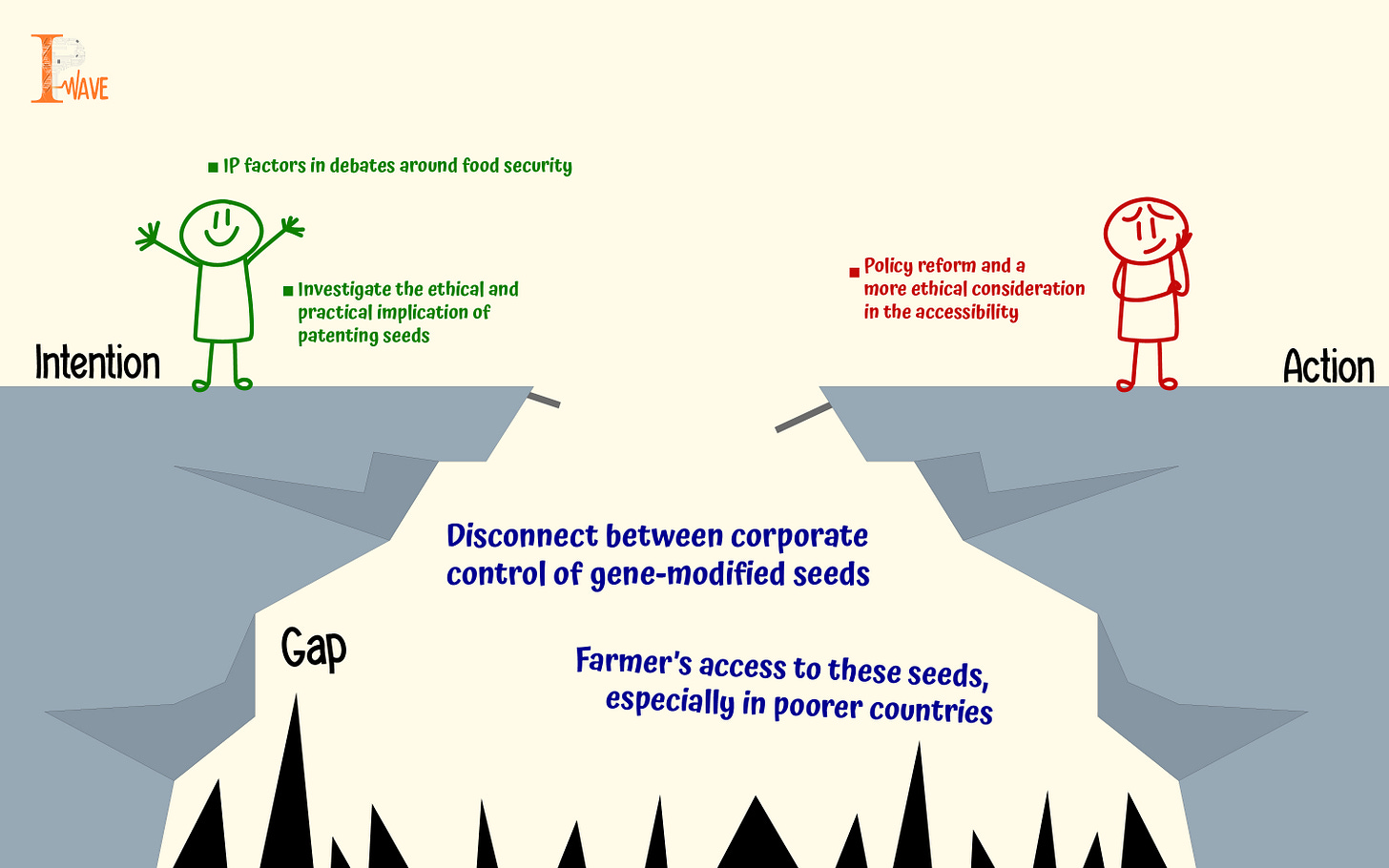

Presently, the entire legal framework stands at crossroads as the climate crisis keeps deepening and food systems appear stretched.

Global crop yields are expected to drop by 30%, as reported by the FAO, populations are exploding and the burden placed on food systems to increase production with reduced resources is as urgent. Climate-resilient crops that will have the ability to transcend extreme weather events is the need of the hour. This does not been modifying the entire seed species but rather making simple tweaks in some strands of plant DNA allowing them to be more adaptive. Sounds like a simple solution to a big problem.

The catch? Most of these seeds are patented and are very expensive to buy. How does a farmer is Andhra Pradesh who can barely make ends meet – find the requisite capital to pay for these seeds? Survival has become difficult.

The question then becomes should intellectual property stand in the way of survival?

The picture is not all gloom-doom. The European Commission has made major changes by banning patenting of gene-edited crops and has also pushed for deregulation. The rationale being simple – survival and food security will not come at the cost of corporate paywalls. Translating this for resource-poor countries is the challenge.

The Global South has also seen major pushback on the issue. While innovation is acknowledged – farming has always been a community practice that involved a free exchange of seeds.

Research and development that has allowed us to make such major strides in creating plants that are high-yielding and climate-adaptive is very welcome and needed. However, excluding the very people this research seeks to help and aid – especially in countries which do not have the resources to pay these prices is undermining its very purposes.

Divya has taken over her father’s land. She looks up and asks “Are there no seeds that work? Are there no seeds that I do not need to mortgage my land to buy? Are we that doomed?”

The world is burning - literally and figuratively. Hunger is increasing and so are temperatures. In a world that is both hot and hungry – who do seeds truly belong to?